HSC nursing professor loses son to fentanyl

- February 27, 2024

- By: Eric Griffey

- Community

Noah Scout Burns just wanted to sleep. His dreams had become a place of dread, punctuated by screams, outbursts and violent flailing. The 26-year-old was tormented by crippling and persistent nightmares after a failed attempt on his life — a bullet pierced his neck but miraculously passed through with minimal physical damage.

Noah Scout Burns just wanted to sleep. His dreams had become a place of dread, punctuated by screams, outbursts and violent flailing. The 26-year-old was tormented by crippling and persistent nightmares after a failed attempt on his life — a bullet pierced his neck but miraculously passed through with minimal physical damage.

Noah survived a gunshot from point-blank range only to be felled by a tiny yellow pill he was given by an old high-school classmate. Desperate to numb his night terrors, Noah confided in this old friend, who also suffered crippling post-traumatic stress disorder. His former classmate offered Noah what he thought was Percocet, an opioid that contains oxycodone. His would-be sleep aid was laced with fentanyl, a deadly synthetic opioid 50 times more potent than heroin.

“After that shooting, he had horrific dreams,” said Noah’s mother, Dr. Rebecca Burns, HSC College of Nursing’s associate dean and chair for undergraduate studies. “I even caught some on video because I thought, ‘Who is going to believe this?’ It was horrid. He was fighting people, begging them to stop hurting him.”

“He didn’t want to sleep because he knew he’d have them, or he wanted to go into a deeper sleep so he would avoid them.”

Like an alarming number of Americans, Noah overdosed on a drug he didn’t know he was taking. Fentanyl is a fine-grained powder, meaning that it’s easy to mix into other drugs.

Historically, drug overdoses in America traced a sad path from recreational drug use to addiction to death. While that still happens, a staggering number of fentanyl deaths are now caused by what officials call “hot” pills — tablets made to look like prescription medicine but instead contain potentially lethal amounts of fentanyl.

Overdoses are now the leading cause of preventable death among people ages 18 to 45, ahead of suicide, traffic accidents and gun violence, according to federal data.

Last year, the federal Drug Enforcement Administration seized 20.4 million counterfeit pills, which experts estimate represent a small fraction of those produced. Its scientists say that about four out of 10 pills contain lethal doses of fentanyl.

Noah wasn’t a typical addict. He self-medicated with Xanax when he felt anxious or overwhelmed, but stopping was never an issue. He wasn’t a thrill-seeker or an everyday user looking for the next high. He wanted to feel normal, happy and put an end to the unrelenting barrage of thoughts that seemed to infiltrate his every moment — whether he was awake or not.

For Burns and other anguished families across the country trying to navigate the whiplash effect of being aggressively shoved into grief, the statistics, headlines and other swirling ephemera around the fentanyl crisis don’t tell the story of what the world lost. They suffer in solitude, balancing sorrow with perseverance, resentment with forgiveness.

Burns won’t allow her oldest son’s legacy to be reduced to a police report or data point. As her mouth tried to keep pace with her brain, she gushed descriptors of her oldest child.

Burns won’t allow her oldest son’s legacy to be reduced to a police report or data point. As her mouth tried to keep pace with her brain, she gushed descriptors of her oldest child.

“He was bigger than life,” she said. “He had a smile that could light up a room. He was the most caring individual that I know — and caring to a fault. He was generous beyond all belief. If he had nothing, he’d still give it to you if he thought you needed it, and he would have less than nothing. He was very caring and giving and smart. He was just so smart.”

“He could take anything apart, put it back together,” she continued. “I used to call him my little MacGyver. He was a creator. He was a developer.”

Noah would have turned 27 in October.

Our family against the world

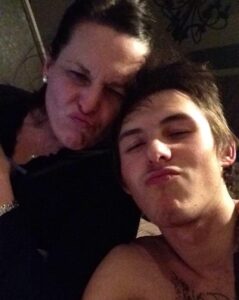

As Burns was swiping through her phone looking for her favorite pictures of Noah, her face conveyed a sense of longing — somewhere between beaming pride and unimaginable sadness — as she found the right ones.

As Burns was swiping through her phone looking for her favorite pictures of Noah, her face conveyed a sense of longing — somewhere between beaming pride and unimaginable sadness — as she found the right ones.

“Our family is very close,” Burns said. “It was always our family against the world. We always said that. Now that’s broken. It’s not whole anymore.”

Noah’s younger brother, Matthew, was days away from asking him to be the best man at his wedding. His sister, Taylor, who was closer in age to Noah, sent her mother a video detailing her struggles with his absence. A note Noah wrote in lipstick remained for months after his death on a mirror in the Burns’ bathroom, “Love you, Pops,” it read. Noah loved his whole family, but he shared a particularly strong bond with his mother.

“When they say grief comes in waves, it really, really does,” Burns said. “I think of him every day when I wake up, every day when I go to bed. But it comes in waves of intolerable sadness and an incomprehensible absence of him.”

The Burns are still mystified at how fentanyl invaded the fortress they had tried to construct from comfortable homes and good schools. Their son’s path to substance use was propelled by trauma and depression — lost to the easy availability of drugs, a false sense of trust and friendship, and a susceptibility to addiction.

The Burns sought help for Noah at age 17 after a rocky romantic relationship plunged him into what his mother described as “the change.” The normally even-keeled teen became quick-tempered and prone to depression and anxiety.

At the time, the family lived in College Station where Burns taught at Texas A&M’s School of Nursing. Mental health professionals are scarce in the South Texas town. To even see a physician meant navigating an obstacle course of red tape that included referrals, waiting lists and bureaucratic headaches. Even with front-line knowledge of the system, Burns was unable to secure a consistent psychologist for Noah.

When Noah finally was on the verge of treatment, his doctor moved out of the area, meaning the family would have to start the long process all over again. That’s when Noah began to self-medicate. His first black-market drug of choice was Xanax, a commonly prescribed depression and anxiety medication.

“We realized when he came home one day, he was impaired,” Burns said. “And, according to him, [Xanax] took his anxiety here to down here,” she gestured. “But then he would just take too much of it. It got to the point where he just wanted to be out of reality a little bit.”

Noah once again struggled through an unstable relationship. He was awoken by a gunshot wound to the neck. His girlfriend at the time was standing over him. Added to the stew of mental health issues, PTSD caused his overall mental health to deteriorate.

Noah moved back in with his parents and, Burns said, he seemed to be doing better for a time. He reconnected with an old friend who had just ended his service in the military.

As Burns would later discover, it was that friend who convinced Noah to use Percocet to help suppress his nightmares.

“He can’t be defined by his mental illness or by this death, because he offered the world so much more than that,” she said. “He was so valuable. And I just don’t think that people understand their value.”

What just happened?

Burns saw Noah come home the evening before his death on her Ring doorbell video. She was looking at the app to see if feral kittens who lived in the neighborhood visited her front porch over the night. Noah parked his truck and came inside around 10:30 p.m.

Burns and her husband tried to strike a balance between giving their 26-year-old son the appropriate space while keeping him close and a part of the family’s everyday life. The two had just spoken about how Noah needed to be more present in the house if he was going to stay there. He was in and out and kept irregular hours, so it wasn’t uncommon for him to stay the night elsewhere, come home early in the morning and sleep through most of the day.

Burns’ husband left for work that morning, and she had a colleague over for coffee before their university’s commencement ceremony later that afternoon. It wasn’t until checking that app for the cats around 8 p.m. that the Burns began to worry they hadn’t seen their son all day. Burns texted Noah, “Are you OK?”

“I went up to his room and my husband said, ‘What are you doing?’ I said, ‘I’m going to check on him. Something’s not right.’ The second step that I took into the stairway, I just felt this overwhelming sense of impending doom.”

Everything after that moment, Burns said, was a blurred panic she relives every day: sirens, emergency medical teams, police, an investigation, she and her husband separated from each other having to answer questions, and more. Those memories come to her like the distorted fragments of a nightmare.

“After that happened, they took him, and my husband and I were left alone in the house,” Burns said. “We just looked at each other like, ‘What just happened? That literally just did not happen. He’s gone. There’s never going be another hug from him.’ There’s nothing to do but clean up the mess, which they left us to do.”

A nation’s response

Fentanyl kills by overpowering the body’s natural instinct to breathe. It binds to a receptor in the portion of the brain that controls breathing and heart rate. There’s only a short window to save someone who has overdosed on the drug. Medications like Narcan can reverse an overdose, and it only takes two or three minutes to kick in.

In August, Narcan became available nationwide without a prescription for the first time. The change, which the Food and Drug Administration approved in March, is part of a growing acceptance of a strategy known as harm reduction. Under that approach, policymakers focus first on limiting the dangers of drugs, not necessarily getting users to abstain.

Widespread distribution of fentanyl test strips can be an effective, if limited, way to reduce the drug’s destructive impact, but they aren’t yet legal in every state, including Texas. A bipartisan bill supported by Gov. Greg Abbot never made it to his desk.

The strips cannot detect how much fentanyl is present, and there may be some fentanyl analogs that the strips do not pick up. Testing fake pills, such as those meant to mimic Xanax or Adderall, is particularly tricky, as fentanyl can cluster in some parts of the pill but not others.

In the 2023 legislative session alone, hundreds of fentanyl crime bills were introduced in at least 46 states, according to the National Conference on State Legislatures. Virginia lawmakers codified fentanyl as “a weapon of terrorism.” An Iowa law makes the sale or manufacture of less than five grams of fentanyl — roughly the weight of five paper clips — punishable by up to 10 years in prison. Arkansas and Texas recently joined some 30 states that have a drug-induced homicide statute on the books, allowing murder prosecutions even of people who share drugs socially that contain lethal fentanyl doses.

A special unit that deals specifically with fentanyl- and opioid-related deaths investigated Noah’s death. The man suspected of supplying the pill that killed Noah was arrested on charges stemming from another case. The Burns family has written letters and submitted text evidence in hopes that Noah’s death is attributed to this person’s actions.

“We had just talked about the dangers of this, and he said, ‘I would never take anything like that,’” Burns said. “He just trusted someone he shouldn’t have.”

“I just think he’s probably so angry right now,” she continued. “The last text I had from him I said, ‘Make good choices.’ He said, ‘I will.’ I said, ‘I love you.’ He said, ‘I love you, too.’”

A new mission

Noah stopped his car in the middle of downpouring rain to help a woman put groceries in her car. He saw a child wandering the streets alone and stayed with him all day until his parents got off of work — even giving the kid his favorite hat. Burns can recall a hundred more stories of her oldest son’s generous spirit and kind heart.

A friend of Noah’s sent Burns a text after he passed.

“He was the most loyal, genuine, intelligent, caring person I’ve ever met,” the text read. “He spoke very highly of you and his family — even showed me videos of you on the news and was just beaming ear to ear.”

Everywhere she looked in her College Station home, she was reminded of her “little MacGyver” — a faucet he fixed or some other appliance he’d taken apart.

“It does tend to make you wonder about a greater plan,” she said, addressing God while speaking about losing her son after he had survived a gunshot. “You want Noah to go through all that suffering, that healing and trauma and all that, and then you still just take him?”

“I feel like God allowed me to have one-on-one time with him between that shooting and when he died. I was with him, and we talked day and night. I stayed up for hours and had a blast with him.”

In February, HSC launched its College of Nursing, which is set to start classes in the fall. Her former boss, Dr. Cindy Weston, was named the school’s founding dean in May. Burns applied and was hired.

When she and her family arrived in Fort Worth, she felt a renewed sense of purpose, she said.

“I’m grieving, but I have a new mission,” she said. “Right after all of that, this great opportunity came open for me to move here and join the Health Science Center and create an innovative program along with Dean Weston to really prepare nurses for these challenges they’re going be facing. And I feel like that wouldn’t have happened if it wasn’t for him. I just feel like he’s guiding this whole thing.”

“It’s just been a whirlwind since then, and I feel like that’s by his design. I just keep moving forward because the alternative is lying in bed with a blanket over your head and just crying, and that just doesn’t work.”

In October, just after Burns started at HSC, the university launched its One Pill Kills campaign in conjunction with Gov. Abbott’s. Burns said she saw that as confirmation that she was where she was supposed to be and that she would continue to draw greater meaning from Noah’s death.

“I am so hopeful,” she said. “That’s what I rely on often: faith, hope and love. And so I just keep going.”

“We all have doubts, and we all question our purpose on this earth. And his purpose …” Burns stopped as she began to break down into tears. “He made us laugh and he was so genuine and just so kind. He was just so kind.”

Social media