DNA dilemmas

By Jan Jarvis

Melody Josserand took an at-home DNA test on a lark, hoping to find out what part of Europe her ancestors were from.

The DNA analyst at UNT Health Science Center knew she was adopted, but says she never was particularly curious about her biological parents.

But as soon as the results came back, her heart began to pound. Listed at the very top of possible matches was someone who shared her DNA. Josserand could stop there and never know who the match was, or she could message the person.

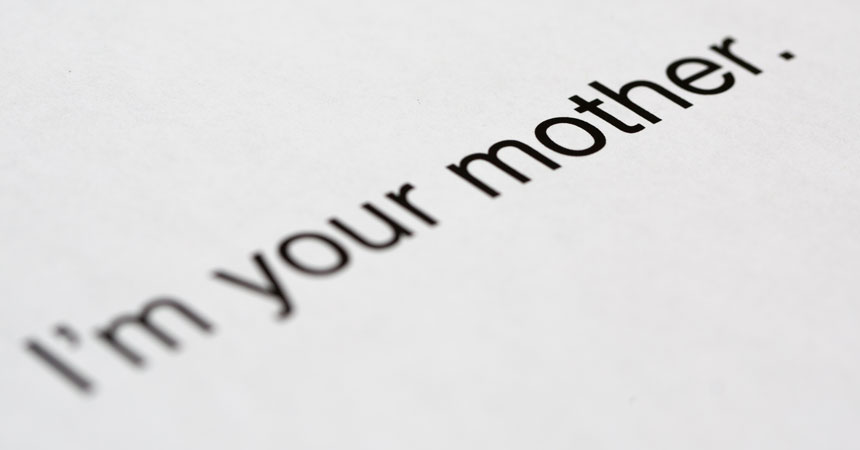

She sent the message. Three days later, after supplying a few details about her birth, she got a reply: “I’m your mother.”

Josserand is among the more than 12 million people who have purchased DNA tests in which a saliva sample is used to survey a person’s genome. For some, the results can be life changing; for others, a waste of money.

Beyond identifying living relatives, the at-home tests have become popular ways to fill in family trees, trace lineages back for centuries or even learn the exact breed of your pet dog. They also have garnered attention for helping solve crimes and mysteries spanning decades.

Along with the tests’ growing popularity have come concerns about privacy, legal issues or the prospect of personal data getting into the wrong hands. People are often ill prepared for the Pandora’s box of possibilities that DNA tests can open.

“Before anyone takes one of these tests, they should think twice about what it could reveal,” said Michael Coble, PhD, Associate Professor of Microbiology, Immunology and Genetics.

Family trees

As a DNA analyst, Josserand said she believes she was better prepared than most people to handle the test results. She stays in touch with her new-found relatives, including two half-siblings, through social media, email and greeting cards.

But even she was surprised by her emotional reaction to finding her birth mother.

“Yes, I had a better understanding of what could happen,” she said. “But that still doesn’t tell you anything about how you’ll feel when find your biological parent.”

If Josserand was jolted, imagine the shock others experience when facing unexpected family news. In one instance, a woman believed both of her parents were of Western European descent until a DNA tests showed she had ancestors from Eastern Europe.

“A paternity test later proved her dad could not possibly be her biological father,” Dr. Coble said. “The biological father was someone who worked at the fertility clinic where the mother had in vitro fertilization, using what she thought was her husband’s sperm.”

Most people who take DNA tests do not get such dramatic news. But as databases grow, so do the odds of unexpected matches.

Both parties have to use the same DNA testing company for a match to occur, Dr. Coble said. So if one person uses AncestoryDNA and another uses 23AndMe, they are not going to connect since the companies do not share their data.

GEDmatch, a database established in 2010, has improved the odds by allowing users to upload their genomic information and search profiles from different companies. In 2018, the site claimed it has helped 10,000 adoptees find their biological parents. It has also been used by law enforcement to solve cases.

Ancestral roots

Millions of people have taken DNA tests hoping to discover their family’s history.

While DNA tests are able to identify close matches, they are not as accurate when it comes to locating remote villages and ancient addresses. Geographic information is only as good as the reference data the DNA company uses, Dr. Coble said.

“If the company has a well-established data base, then you might find a very good approximation of where your ancestors came from,” he said. “Otherwise, it’s the company’s best guess.”

The odds are better for the estimated 70 percent of Americans whose ancestors are from Europe. Someone whose ancestors are from Africa, Central and South America or Asia are likely to face a tougher time because of a limited number of people who are in the databases.

The world has changed so much over the centuries that is makes it difficult to pinpoint where someone’s ancestors are from, Dr. Coble said. Migration in the last 100 years alone has added to the challenge of locating remote villages and small towns.

“There once was a company that claimed they could identify which tribe your ancestors came from in Africa,” Dr. Coble said. “The unfortunate stain of slavery and the diaspora of tens of millions of individuals makes this claim a bit dubious.

“If you’re hoping to discover exactly where you came from, well, that’s a little tenuous.”

Criminal cases

Joseph James DeAngelo never sent his DNA to an online genealogy service, but at least several of his relatives did.

That proved to be his undoing. DeAngelo, a former police officer, now faces charges for crimes connected to California’s notorious Golden State Killer and is suspected in dozens of rapes and murders in the 1970s and 1980s.

DeAngelo might have escaped arrest had it not been for a relative’s DNA that was stored in the public site GEDMatch. Finding the match was still a huge long shot.

“It’s not like you get the name of the killer as a match,” Dr. Coble said. “This entails the building of a large family tree and then trying to find a list of men in that family tree who were the right age, at the right location, at about the right time of the crimes being committed.”

The first candidate was not DeAngelo but instead a man who was retired and living in Oregon. A DNA test quickly ruled him out.

But eventually investigators zeroed in on DeAngelo and collected a DNA sample that he unknowingly left in a public place. That sample was matched to evidence from multiple rapes and homicides.

The case has focused a lot of attention on how DNA testing can be used to solve crimes. DNA can be stored indefinitely, which can raise privacy issues down the road. Individuals who store their DNA on GEDMatch are made aware that their genetic information could be used by law enforcement, Dr. Coble said.

Doggy DNA

DNA tests have found another commercial purpose: helping pets owners identify the breed of their dogs.

Darlene is a fluffy, friendly black dog who was dumped at a mobile home park in Weatherford. When Jill Johnson adopted the pooch, she suspected she was a Labradoodle. DNA test results showed Darlene was a combination of American Staffordshire Terrier, poodle and cocker spaniel.

“I was just dumbfounded by the results,” said Johnson, a UNTHSC photographer. “They just seemed way off.”

What is true for humans is true for dogs, Dr. Coble said. DNA results are only as good as a company’s database. Companies with the largest databases can recognize more than 350 breeds, including wolves and coyotes.

People should enter the world of DNA testing with their eyes wide open.

“The real power of these tests lies in the ability to identify close relatives,” Dr. Coble said. “These DNA tests can end up telling you things you may have never wanted to know.”

Social media