Fighting a deadly side effect of heart failure

For many of the 6.5 million people who live with heart failure, developing water retention related to their disease will decrease their chances of survival.

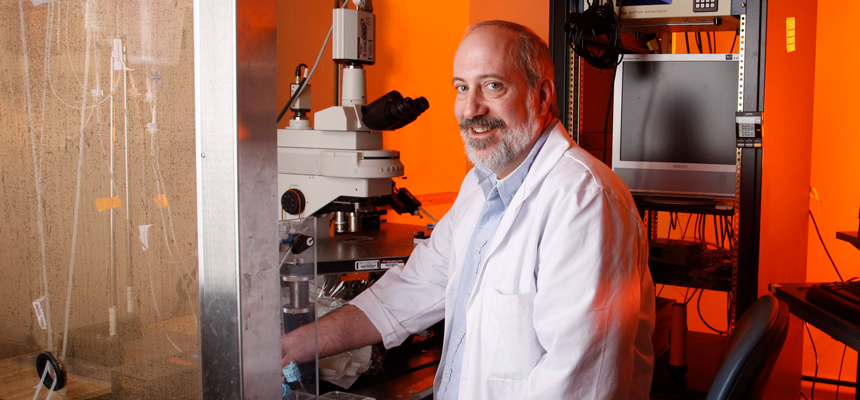

Although many patients with water retention are treated with diuretics, it is not known why they develop the condition, said Tom Cunningham, PhD, Regents Professor of Physiology & Anatomy.“Drugs treat the symptoms, but not the possible cause,” said Dr. Cunningham, Interim Associate Dean, Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences.

“We want to find a way to understand and prevent the problem in the first place.” Dr. Cunningham has spent much of his career trying to address such problems and better understand homeostasis – or how the body maintains its internal equilibrium. His work in this field was recently recognized on two fronts.

First, he was received a $2.2 million grant from the National Institutes of Health, which will be used to further his research on vasopressin, the so-called antidiuretic hormone. The body makes this hormone on its own to help regulate water loss and maintain adequate hydration.

He also received the Leonard Share Award of the Water and Electrolyte Homeostasis (WEH) Section of the American Physiological Society (APS). The award honors WEH members who exemplify Dr. Share’s commitment to the APS and dedication to research in integrative physiology.

In his study of vasopressin, Dr. Cunningham and others have tried since the 1980s to find out why it is abnormally released in some patients with heart or liver failure, causing life-threatening water retention. The grant from the NIH will allow his team to study a new mechanism that they recently discovered working with other laboratories from Canada and New Zealand.

He compares it to a car that malfunctions. Most biological systems have an accelerator and a brake that allow the system to be normally regulated and keep the body functioning normally. In diseases of water retention, most research has focused on vasopressin’s accelerator, Dr. Cunningham said.

“What we have reported is that the problem may be with the brakes,” he said. “That at a cellular level, the brake has been turned into another accelerator.”

If his theory proves correct, it could explain the problem of why once it is turned on, it cannot be turned off. That can lead to better ways to prevent the fluid build-up.

The Leonard Share Award that he has received reflects that same commitment to understanding homeostasis and how vasopressin works in heart or liver failure.

While Dr. Cunningham said he was caught off guard when his name was announced at the award ceremony, others said it is no surprise that he received it.

Dr. Cunningham was nominated for the award because of his long-standing success in his research on the neural control of vasopressin release, and his continuous support of the APS and the WEH Section of the APS, said Carmen Hinojosa-Laborde, PhD, WEH Section of the APS Chair.

He has taken on numerous roles over more than a decade, including WEH Secretary/Treasurer, Representative to the Joint Programming Committee of the APS and the APS Career Opportunities in Physiology Committee.

“Like Dr. Leonard Share, Dr. Tom Cunningham is humble and modest about his service to the APS,” she said. “He is truly one of the WEH section’s unsung heroes.”

Social media